The Tash-k’irman Fire Tepe Temple

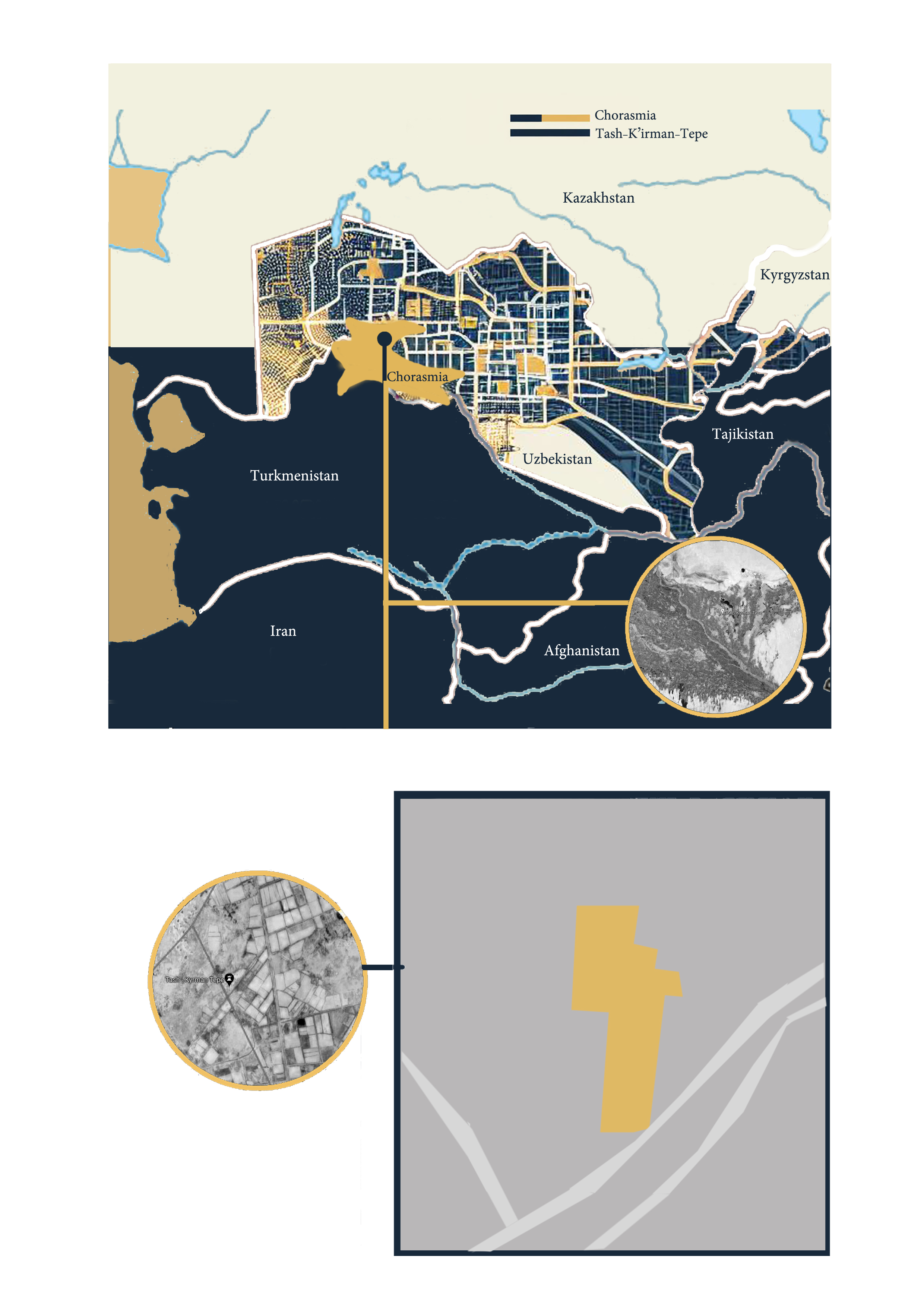

Tash-K’irman-tepe is a Zoroastrian fire temple complex, Uzbekistan, seven kilometres east of Akchakhan-Kala in the delta of the Amu-Darya in the ancient Chorasmia, a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire in Persia and was ruled by the satrap of Parthia. The Chorasmia region is now called Khwarazm and belongs partly to Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in West and Central Asia. (Figure – 1: Location, site map)

Tash-k’irman-tepe is one of the several structural complexes believed to be linked with the worship of fire in Uzbekistan. The Tash-k’irman oasis appears to be the last remaining relatively untouched archaeological zone in the ancient Chorasmia region. Records of the Chorasmian Archaeological Expedition show that intensive agricultural exploitations under the Communist regime in the former Soviet Union destroyed most of the archaeological sites.

As the scale and architectural style of the Tash-k’irman-tepe indicate, it was one of the main religious centres of ancient Chorasmia and was likely built in the seventh or sixth centuries B.C. Some researchers suggest that the prophet Zarathushtra ruled Chorasmia in about 588 B.C., therefore this fire temple might have been associated with Zarathushtra’s ministry in Chorasmia.

The Tash’k’irman-tepe temple’s significance also lies in revealing the history of pre-Sasanid fire rituals in Zoroastrianism. While the monuments of Ancient Chorasmia appear to lack stepped fire altars of traditional type such as those depicted on Achaemenid royal rock reliefs or Sasanian coinage, they are not lacking in other unusual features associated with fire. They demonstrate fire features before the Sassanid times as an important backdrop to later practices related to fire temples in Zoroastrianism.

Site Location

Until around the 7th century B.C., the Amudar’ya river delta (classical Oxus) was part of an Inner Asian culture dating back to the second millennium B.C. After that, a sudden cultural, political, and demographic change took place in the later 7th or early 6th century B.C., leading to the notion of adaption of Chorasmia in northern Central Asia. The name Chorasmia appears in Zarathushtra’s book (Avesta) and the Achaemenid taxation list of Darius I, a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire. The Oxus Delta was incorporated into the empire under Darius’ consolidation programme after about 525 B.C. The ancient Chorasmia became a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire in Persia and was ruled by the satrap of Parthia.

During Kangiui early period from 4th BC to, till the late period in the 2nd century BC and early 1st century AD, the region saw the establishment of several large centrally sited fortified and military places, including three or more frontier towns, many border fortresses, at least one “nomad wall”, and rural installations with irrigation systems.

In addition to those fortified establishments, at least one regional religious centre was built, the fire temple Tash’k’irman-tepe. Based on Radiocarbon dating found on the site, The current temple may be dated within the ‘Antique’ period between about 378-235 B.C. This date range refers to a sample from ash layers about 40 cm above the pavement in the temple, however, an ‘Archaic’ period pottery has been found in surface collections from the general vicinity of the site, and the foundation date of the earliest structures has not yet been established.

Then

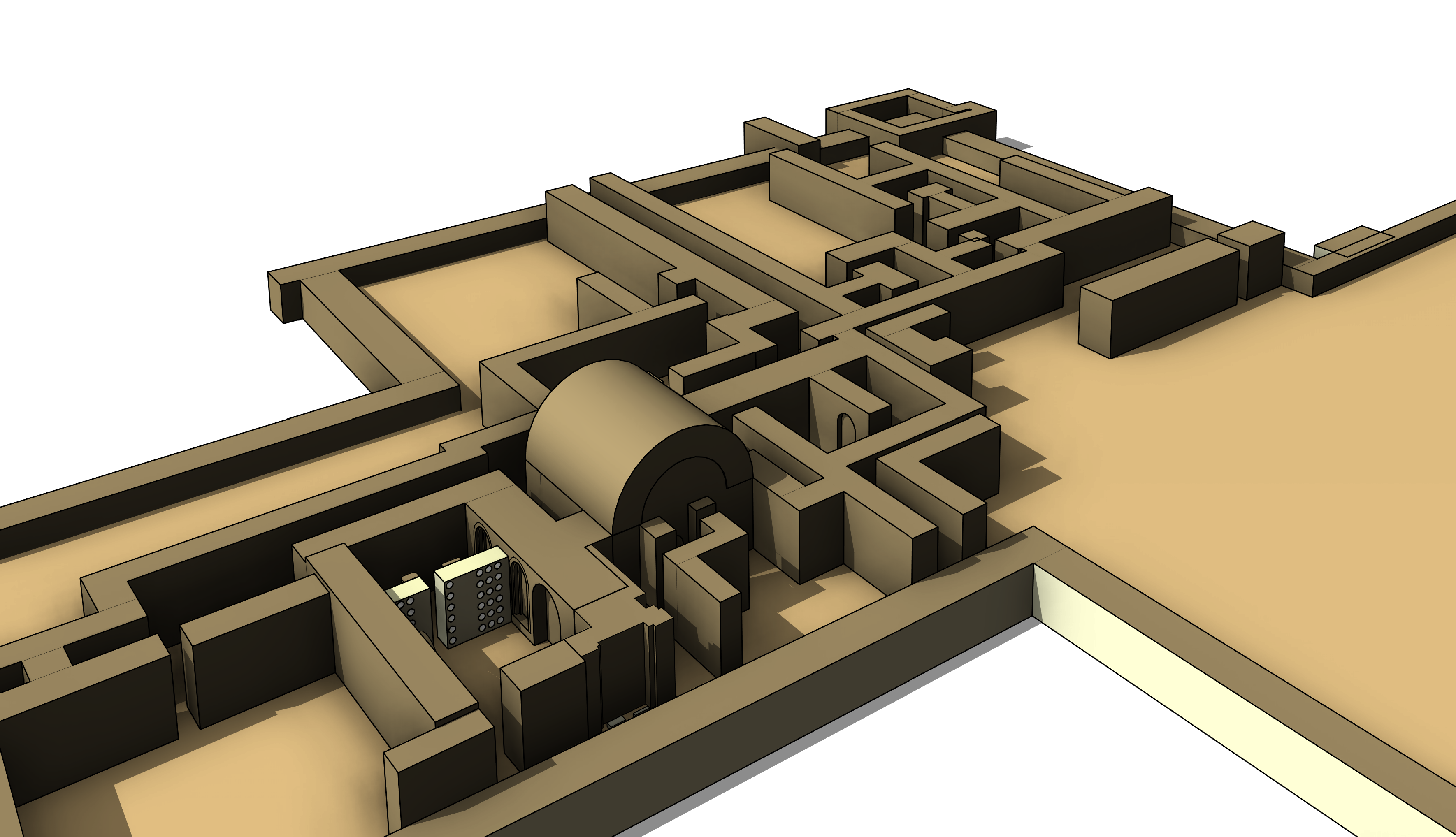

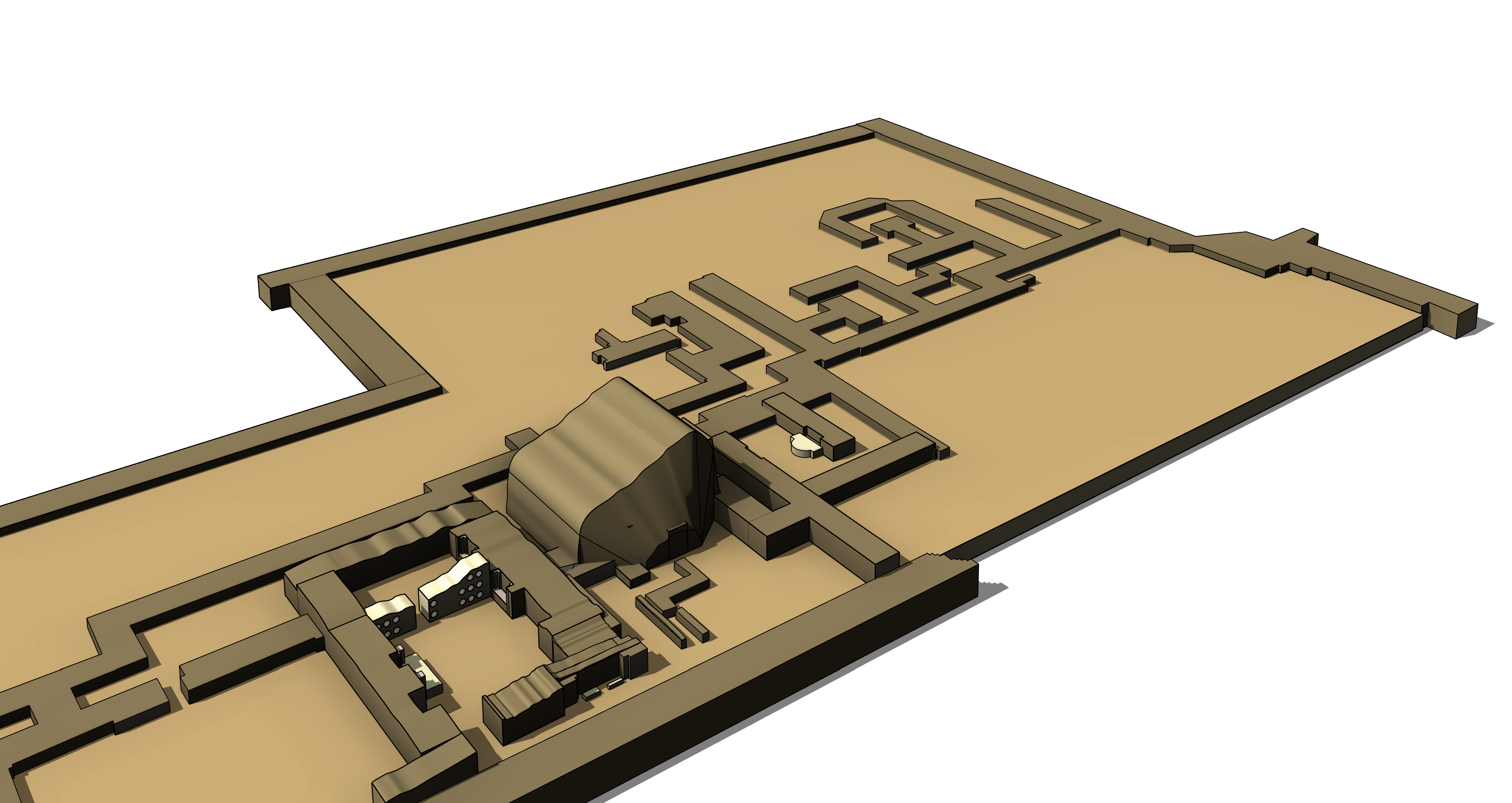

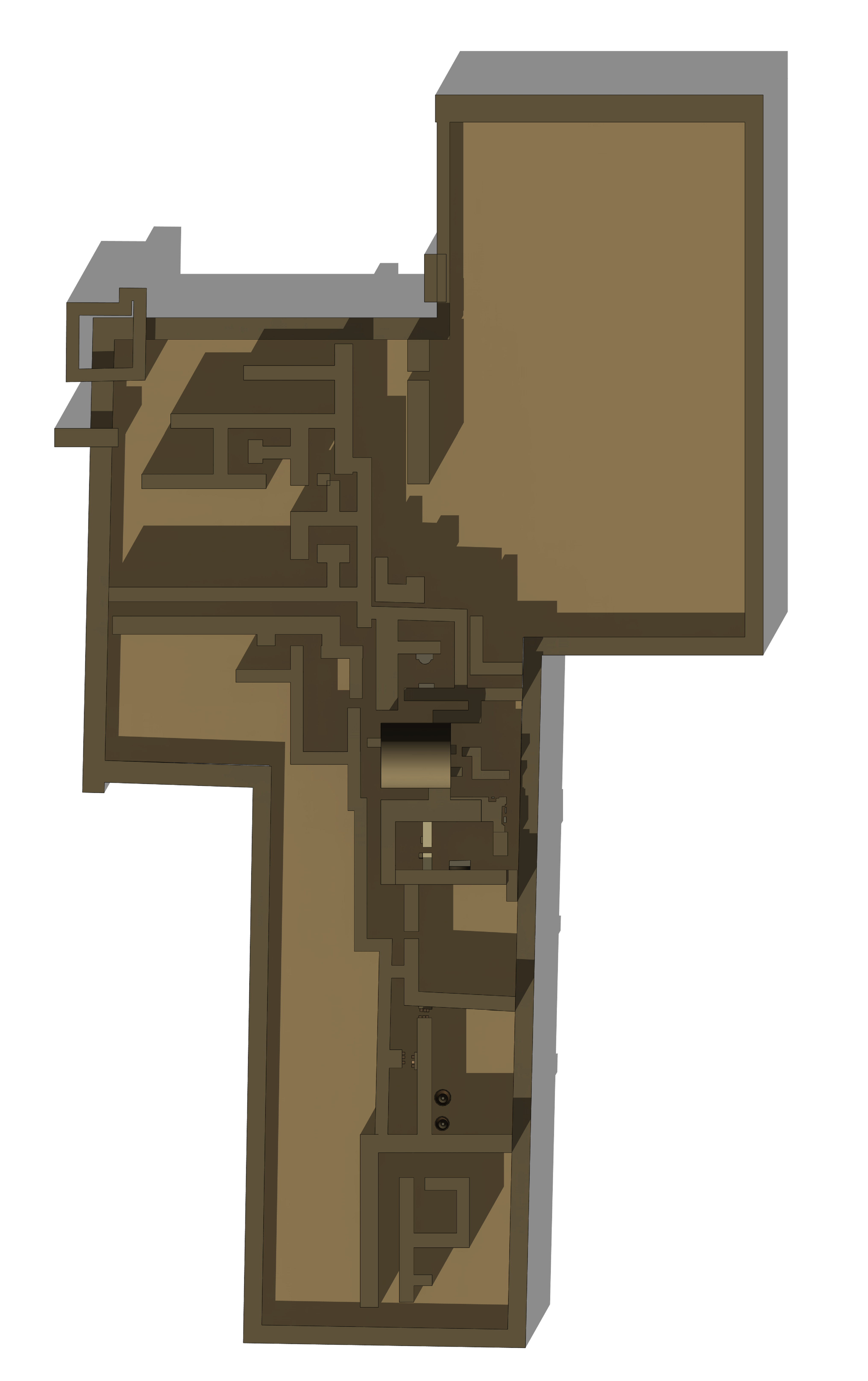

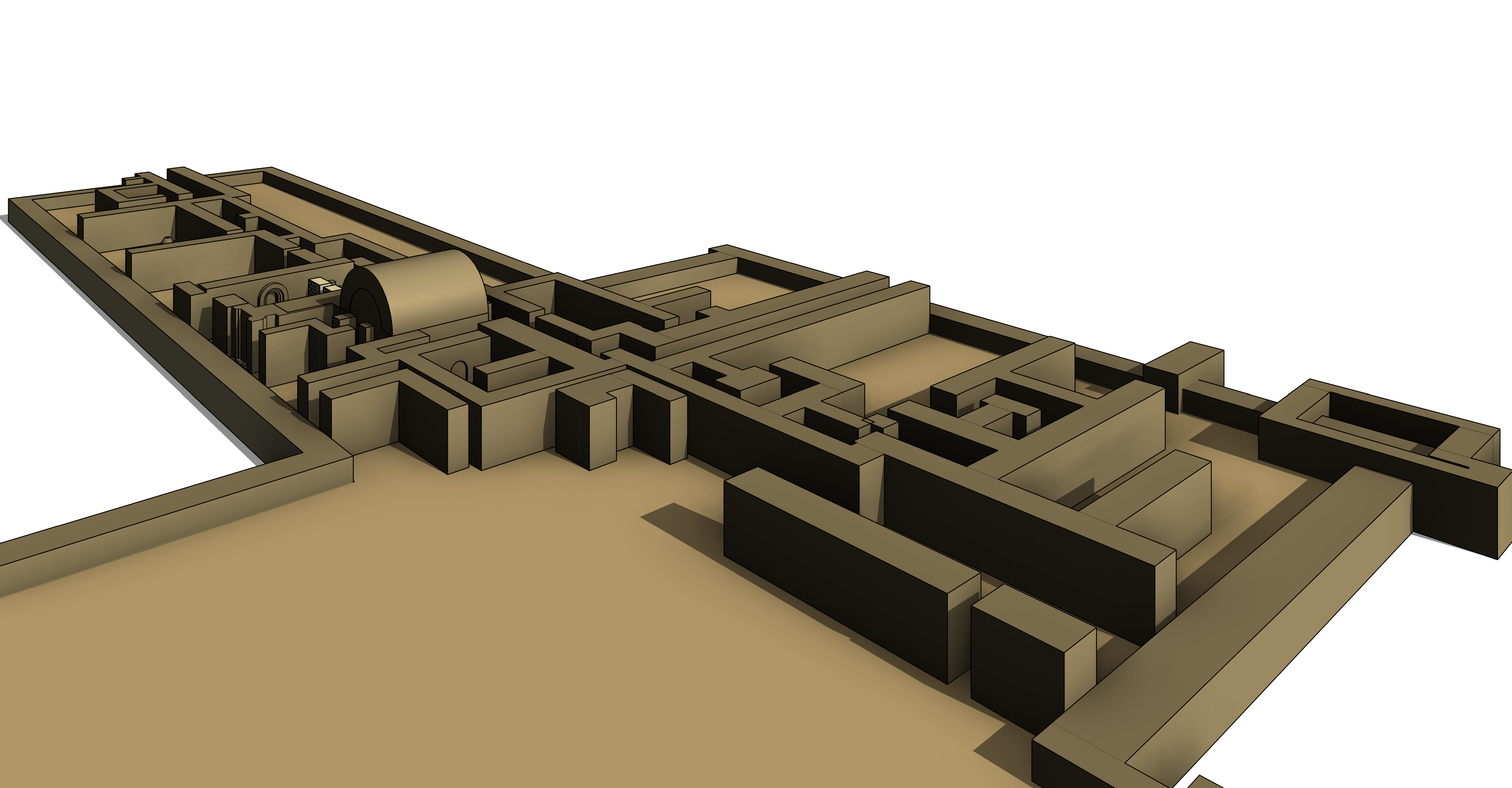

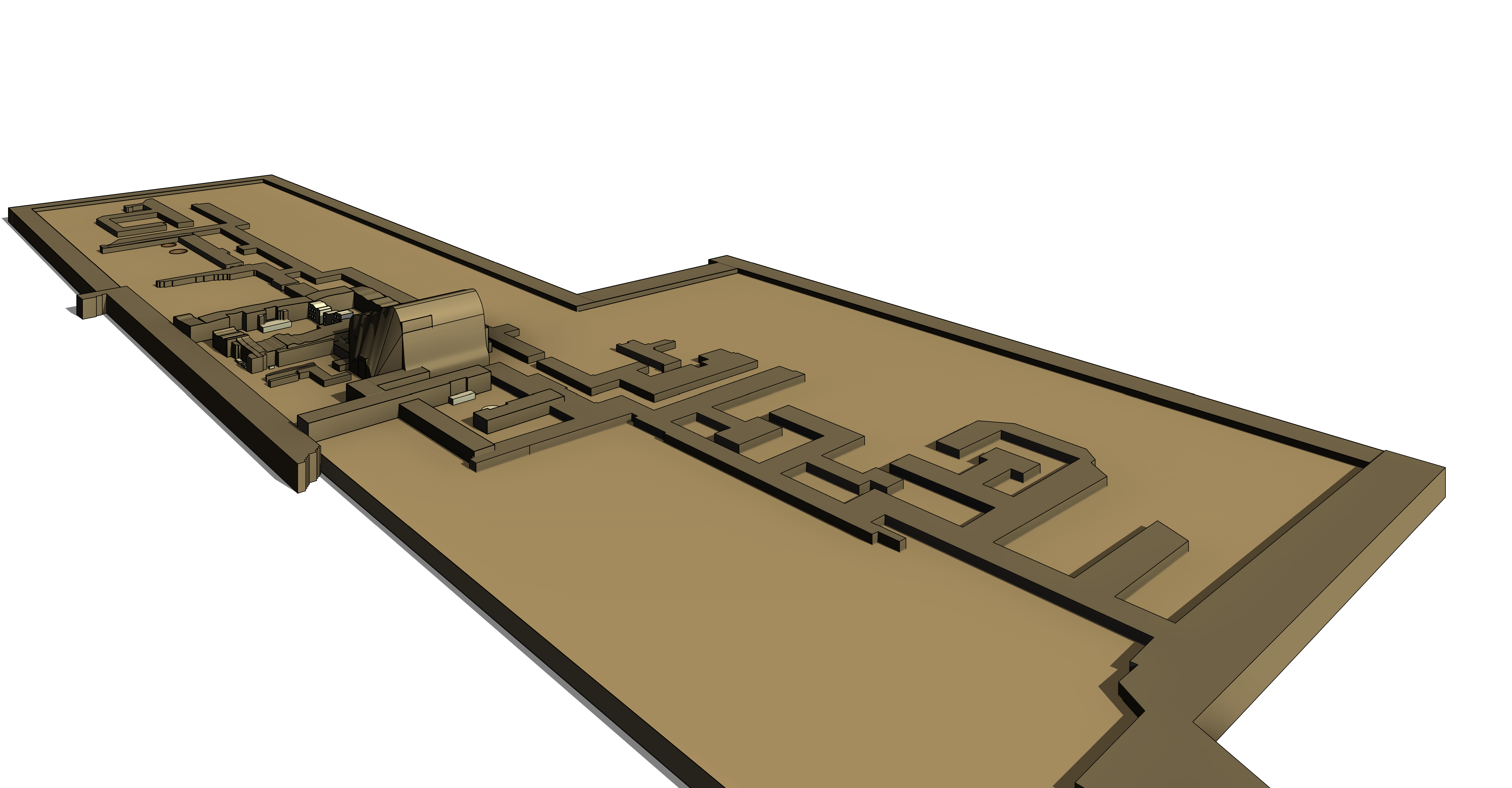

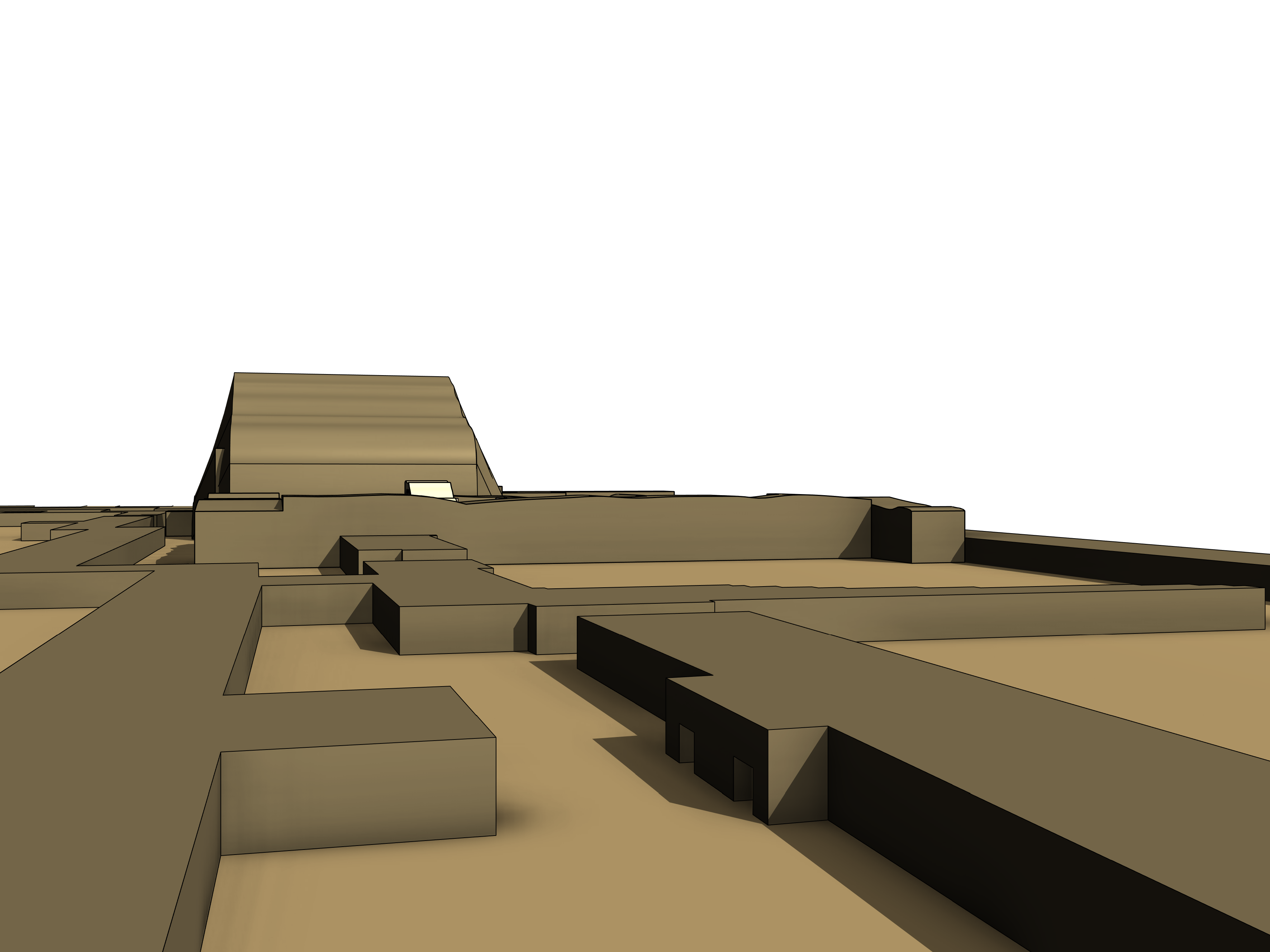

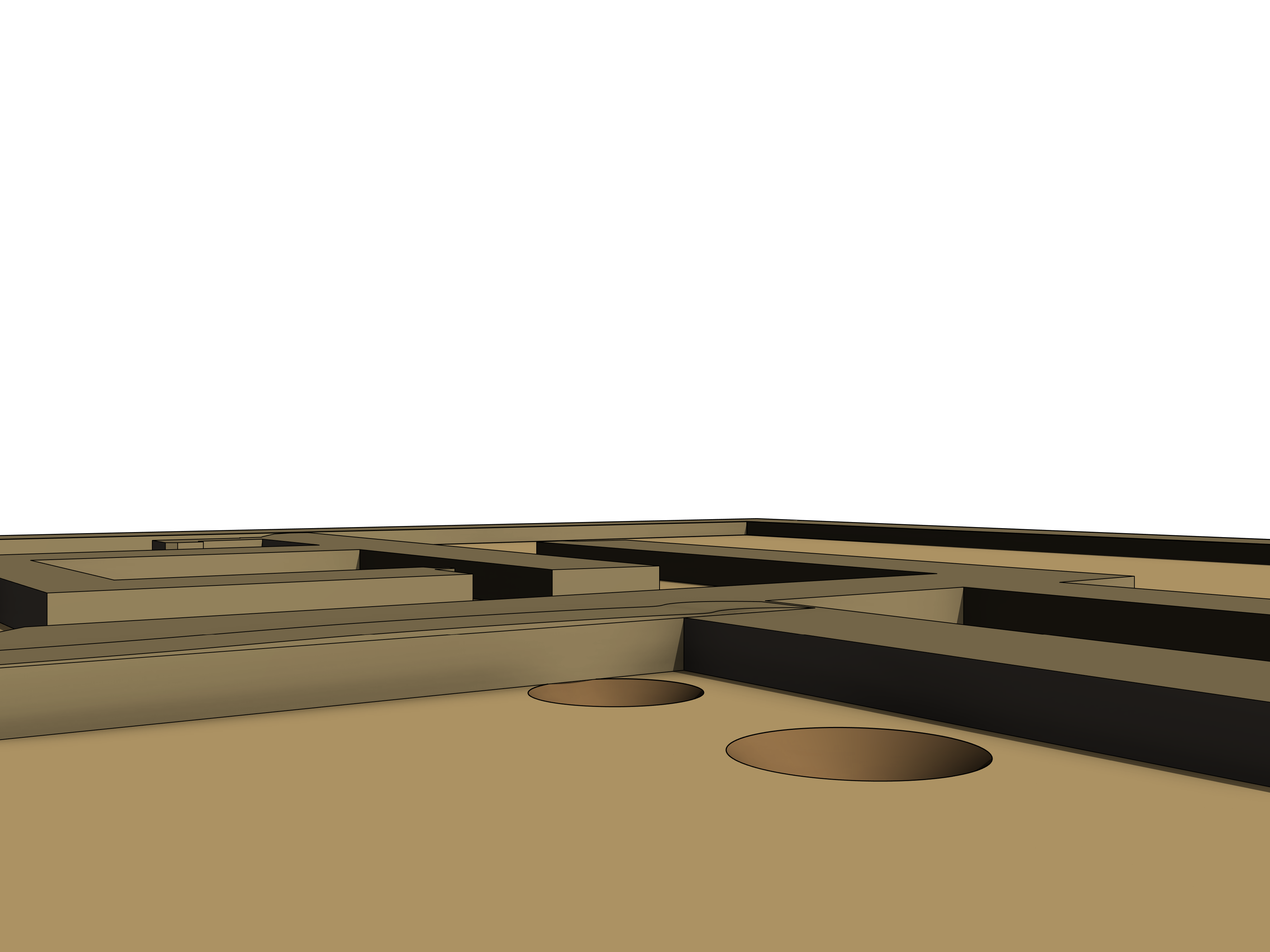

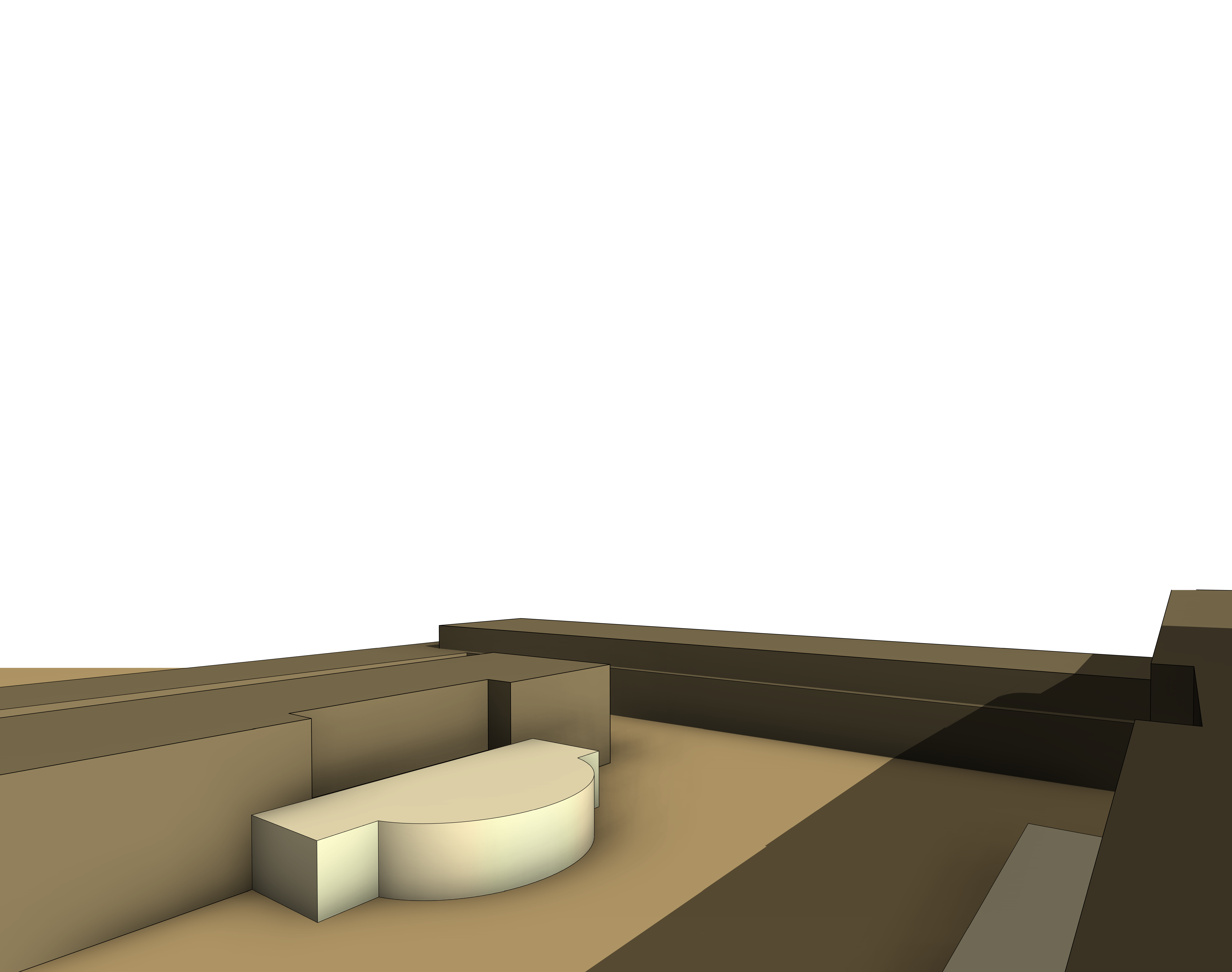

The temple complex (Figure 2: Site plan) stands isolated in countryside and is not associated with any large settlement. It had two major parts, namely a raised platform and the building constructed on the platform. The raised platform was bounded by pakhsa walls. The uppermost layer of the platform was made of complete bricks, carefully laid to form a smooth even surface. The platform was oriented almost directly north-south and is roughly 110 m long. The width varies from 30 m at the southern end to about 50 m at the widest point across the centre. The structures were built directly on this surface. (Figure 3 – 4: eye-bird perspective).

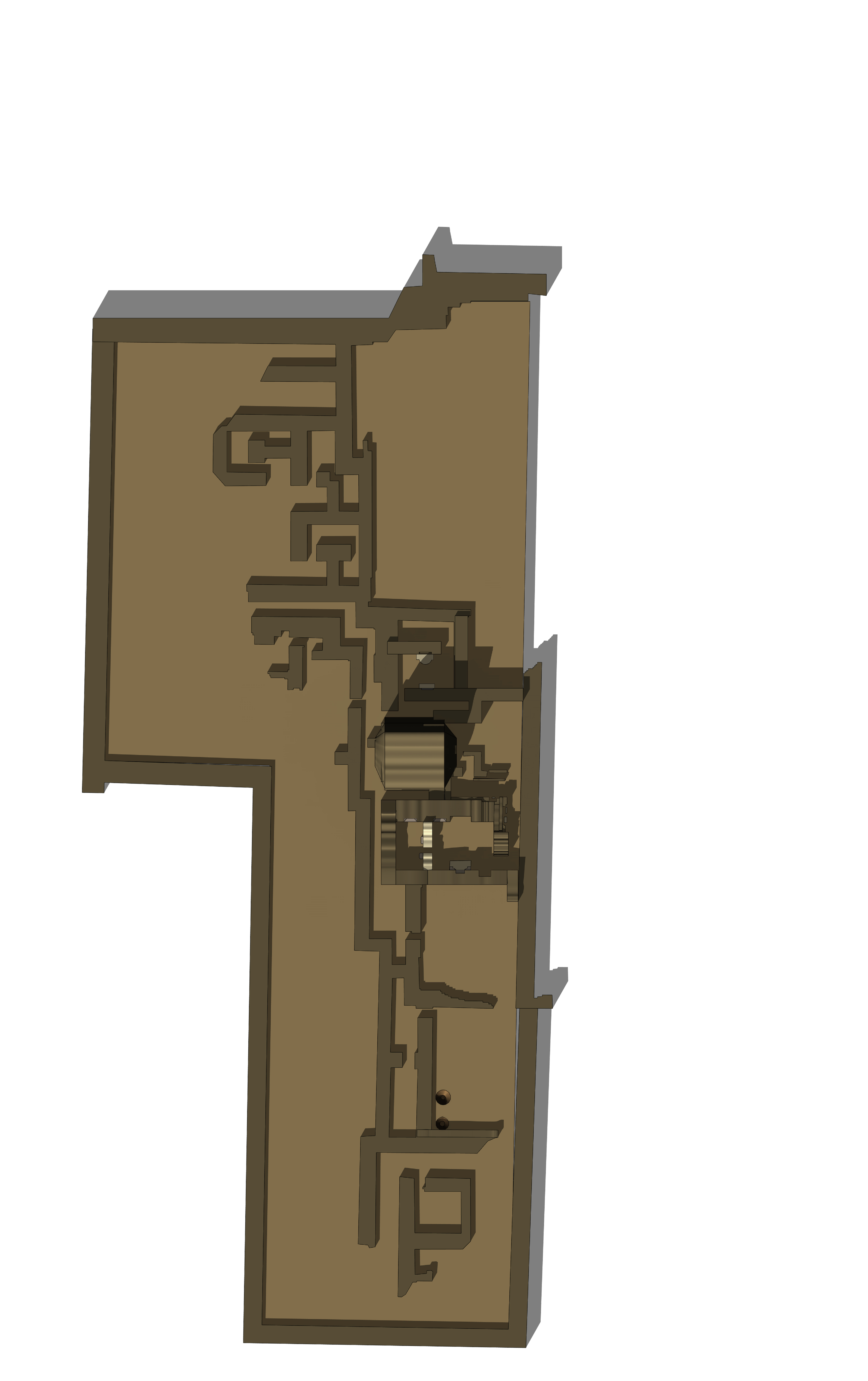

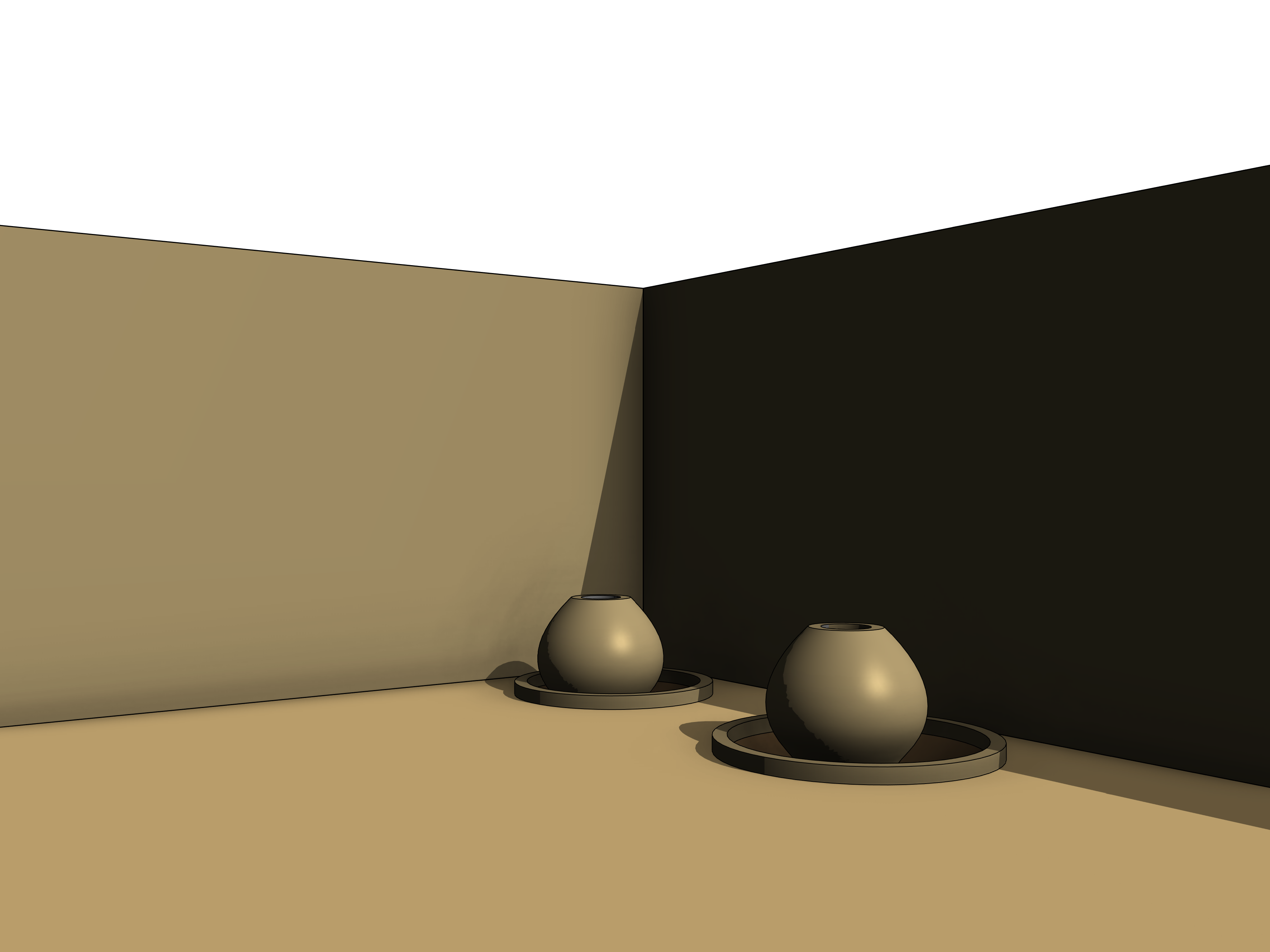

Architecturally, the temple was almost devoid of any ornament, however, it had unique fire features and evidence of the religious ritual practice with strong cultural value. One of its key features is the extensive and deliberate ritual disposal of ash. Burning doorways at Tash-k’irman-tepe were also unique features with two one-meter walls, made of mud brick with a layer of clay, and a 1.2-meter passageway. Wooden poles were set into the clay, serving as braziers that burned down. Traces of charred poles and heat-reddened rings in the clay were found indicating fire use. The doorways were likely for a ritual purpose. Two examples found for this feature are in the southern part of Tash-k’irman-tepe. One in a corridor-like chamber, divided in the middle by short walls creating the “burning doorway”. The other led to an open chamber with an altar with up-turned jar. Excavation did not reveal the chamber’s function. (Figure 5: the specified rooms)

The altars with up-turned jars were also a distinctive feature. Close beside the fire, a jar was placed, where its base had been broken off and the top inverted and set into a pit over a bed of sand. This had been used as a receptacle for hot ash from the fire. It is supposed that water was poured onto the ash to cool it, the water draining out into the sand through the neck of the upturned jar. The ash could then be removed, possibly to be disposed of in a ritual practice. It was found in a large, apparently open, chamber in the southern half of the complex, with no other features in the room. The fire was set in a round pit, surrounded by a low ring of clay. The room in which the “altar” was located could only be accessed through two ‘burning doorways’, again lending weight to a ritual interpretation of the altar function. (Figure 6: the specified rooms)

The plan of the structures was irregular, consisting of a series of corridors, rooms and courts, most of which as research reveals do not seem to have been roofed, unless perhaps with timber and straw. This is why the building was so eroded, except for the central chamber. While it may seem odd not to be roofed in a country where the climate is characterized by very cold winters, with averages below freezing, and hot summers, it may be interpreted as being only used for special occasions like governmental ceremonies or special spirituals like spreading the sacred ash.

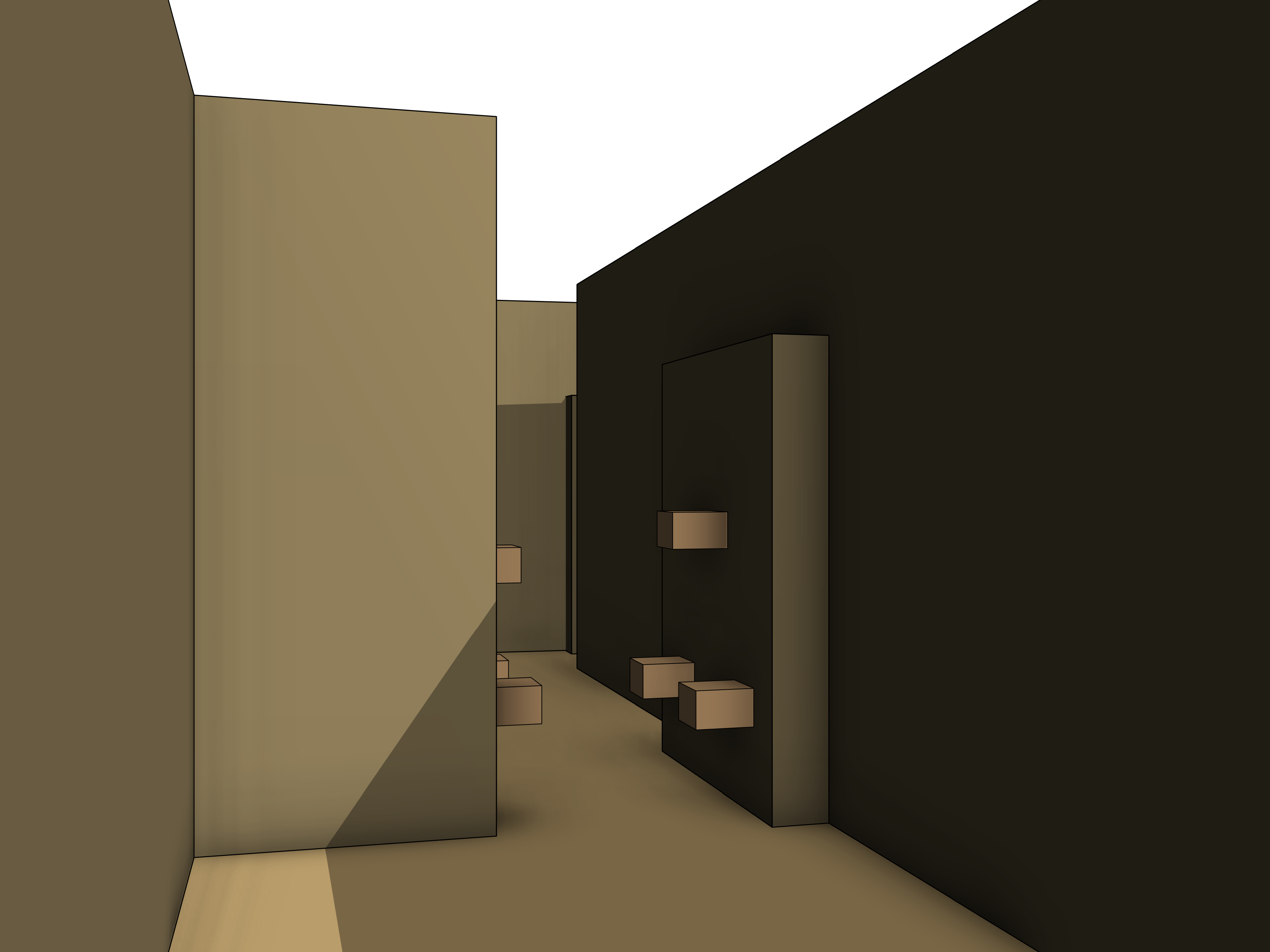

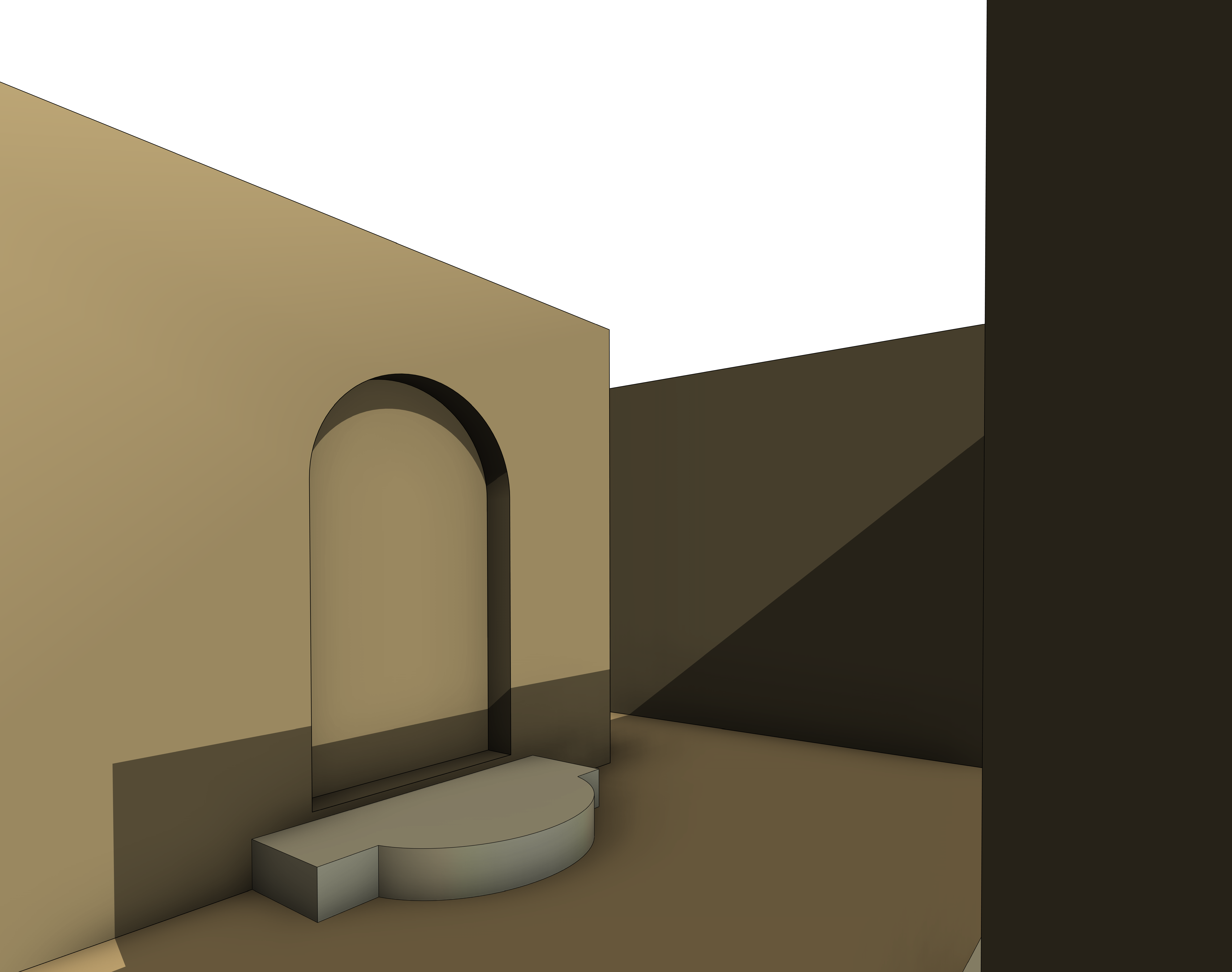

The central chamber which held the sacred fire, was covered by a vaulted roof, as part of the brick arch has been preserved. The central chamber had two entrances on the southern end of the east and west walls. The room held what seems to have been a ritual fire. The fire was set directly on the platform against the east wall with no trace of an altar. Opposite the fire was a recessed niche in the western wall. (Figure 7: section of the Central Chamber) The chamber had no windows and, unlike the rest of the buildings, the walls had no mud plaster surfacing but were simply bare brick. The only exception was the niche, the sides of which were plastered. The whole chamber gave the impression of a private space used simply for keeping the fire but not for any public ceremony.

To the north of the central fire chamber was another smaller but less elaborate altar room. A small brick altar was set close to floor level at the base of a shallow niche in the south wall. (Figure 12: 3D Render of the niches). A narrow entrance led to a further chamber with no other exit. To the north and south of the central complex were various rooms, corridors and courts of uncertain function. Some T-shaped walls may have served as subsidiary altars, while one room held the remains of large ceramic vessels partially set into the floor as up-turned jars altars.

Now

The Tash-k’irman-tepe have seen a series of renovations throughout its life, the latest one could probably be associated with the Late Kangiui or very early Kushan (1st century AD), including blocking doorways and corridors, refacing walls, and changing in the fire rooms. At some point, the complex was abandoned for a time. Before this abandonment, the central fire chamber was deconsecrated. A layer of bricks was laid down over all but at the southern end of the chamber. This was covered with a bed of reeds and then 22 layers of bricks were carefully placed on top until the fill reached the base of the vaulted roof. The bricks were set in sand except at the southern end, where the last two rows were set in mud plaster to form a wall face binding the rest of the fill in place. It is argued that this was done to protect the sacred nature of the chamber and was a case of deliberate deconsecration.

In the Late Kangiui period, there seems to have been a period of disuse at the site as the corridors surrounding the chamber gradually filled with layers of silt up to 50 cm deep. The reuse of the temple’s spaces centred on the southern part of the complex while the remaining northern rooms were used for ash storage. Ceremonial activities were conducted in the southern altar chamber, which was

Project challenges and reflection

The pre-Sassanid Zoroastrian practices are underexplored and under-studied, and extracting architectural features and dimensions required significant efforts. Many spatial aspects associated with those religious and cultural rituals were difficult to determine. This was especially the case for the 3D digital modelling of the ‘Then’ which presents the historical past of the temple.

The latest photos and information for modelling the ‘Now’ situation were extracted from the articles, the latest is from 2018, and no new photos were accessible to the team. Although, the aerial photos from Google Earth show a continuous neglect of the site.

Acknowledgments

The ‘Then & Now’ Team are grateful to architect Behmard Khosravi (Iran) for much helpful advice on interpreting Zoroastrian practices and rituals; and Professor Alison Betts (University of Sydney) for much valuable help and explanation about the site features.

Bibliography

- Betts, A. V., Khozhaniyazov, G., Weisskopf, A., & Willcox, G. (2018). Fire Features at Akchakhan-kala and Tash-k’irman-tepe. Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia, 24(1-2), 217-250.

- Betts, A. V., & Yagodin, V. N. (2008). Tash-k’irman-tepe Cult Complex: An Hypothesis for the Establishment of Fire Temples in Ancient Chorasmia. In Art, Architecture and Religion Along the Silk Roads (pp. 1-19).

- Betts, A. V., & Yagodin, V. N. (2007, January). The Fire Temple at Tash-k’irman Tepe, Chorasmia. In PROCEEDINGS-BRITISH ACADEMY (Vol. 1, No. 133, pp. 435-454). Oxford University Press.

- De Jong, A. (2015). Religion and politics in pre‐Islamic Iran. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism, 83-101.

- Helms, S. W., Yagodin, V. N., Betts, A. V., Khozhaniyazov, G., & Kiddi, F. (2001). Five Seasons of Excavations in the Tash-K’irman Oasis of Ancient Chorasmia, 1996–2000. An Interim Report. Iran, 39(1), 119-144.

- Minardi, M., & Khozhaniyazov, G. (2011). The Central Monument of Akchakhan-kala: fire temple, image shrine or neither? Report on the 2014 field season. Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 25, 121-146.

Disclaimer: The images and architectural modelling shown here are for illustration purposes only and may not be an exact representation of the property. Silk Cities is not liable for subsequent updates, errors, or omissions of data or any update on the conservation on the property afterwards.